Posterior Instability

Henry Fox MA, Cory Stewart MD, Michelle Chang BS, Jon J.P. Warner MD (February 2016)

Shoulder instability occurs when the humeral head (ball) moves out of the glenoid (socket) during motion of the shoulder. This is associated with symptoms such as pain, and sometimes a sense of shifting, looseness, or instability. “Dislocation” is when the ball moves completely out of the socket. “Subluxation” is when the ball moves partially out of the socket.

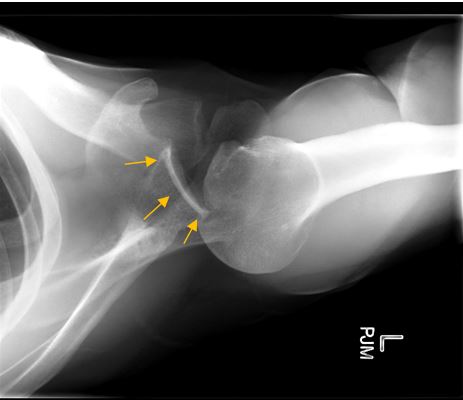

This x-ray demonstrates a posteriorly dislocated shoulder. Rather than the correct orientation in the glenoid (orange arrows) the humeral head has moved out of the back of the shoulder joint. This was due to a traumatic event.

These dislocation or subluxation events can occur as a result of a traumatic event, like a football tackle or fall. Certain positions make it more likely that a posterior instability event will occur, and an example is a football offensive lineman, who has the repetitive stress of receiving a large force with his arms up.

Instability can also occur over time with repeated motions that stretch the ligaments in the shoulder, allowing the ball to move partially out of the socket. For more general information on general shoulder instability, please visit the Instability page.

“Posterior” refers to the back of the shoulder. Thus, posterior instability is when the shoulder is unstable in the direction of the back of the shoulder.

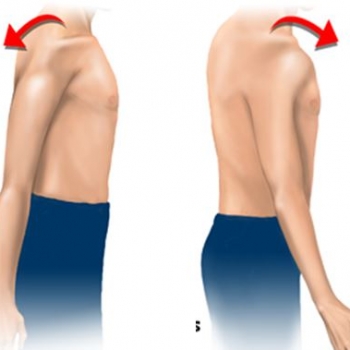

The figure on the left depicts the movement of posterior dislocation (in the “back” direction). The figure on the right shows the movement of anterior (“front”) dislocation.

Shoulder joint instability is common, and affects approximately 2-5% of the population. However, posterior instability is uncommon. Articles have reported that posterior instability occurs in 2-10% of those with shoulder instability. (1) (3).

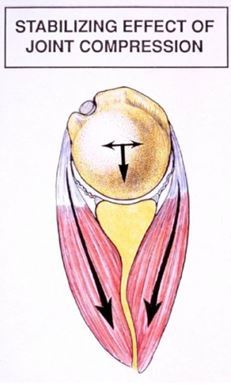

The shoulder is the most mobile joint in the body, but this also means that it is the least stable. Several aspects of the shoulder joint keep the humeral head (top ball of the arm bone) properly secured in the glenoid (joint socket). The balance between mobility and stability of the shoulder depends on a complex interplay of dynamic elements (Rotator cuff muscles and scapular muscles) and static elements (ligaments, labrum, cartilage). As the arm moves overhead for sports and other activities the muscles govern not just movement but also stability as they compress the ball (humeral head) into the socket (glenoid). The scapular muscles move the socket into an orientation which maintains stability.

In a normal shoulder, the humeral head (ball) remains centered (red arrow) on the socket (glenoid, blue arrows). This occurs at all arm positions because the scapula moves in properly coordinated rhythm with the shoulder joint motion. In addition, this stability occurs because the muscles of the shoulder contract and push the ball and socket together (below). This is called Dynamic shoulder restraint, stability provided by muscles around the joint. These muscles include the rotator cuff, the deltoid, and the biceps tendon. Stabilization is also provided by the trapezius, serratus, and latissimus dorsi muscles.

In a normal shoulder, the humeral head (ball) remains centered (red arrow) on the socket (glenoid, blue arrows). This occurs at all arm positions because the scapula moves in properly coordinated rhythm with the shoulder joint motion. In addition, this stability occurs because the muscles of the shoulder contract and push the ball and socket together (below). This is called Dynamic shoulder restraint, stability provided by muscles around the joint. These muscles include the rotator cuff, the deltoid, and the biceps tendon. Stabilization is also provided by the trapezius, serratus, and latissimus dorsi muscles.

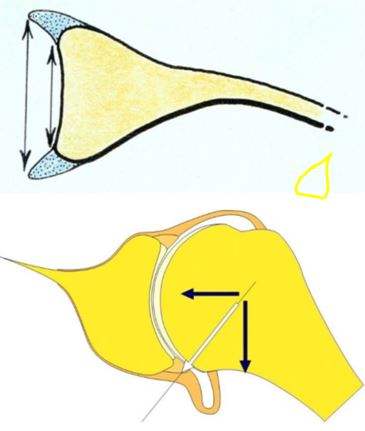

The static ligaments and labrum act as the “seatbelts and airbags” of the shoulder preventing excessive motion of the ball out of the socket.

The static ligaments and labrum act as the “seatbelts and airbags” of the shoulder preventing excessive motion of the ball out of the socket.

Figure 2: The labrum (light blue in the top image) widens and deepens the shoulder socket. It is also an important anchoring point for the ligaments of the shoulder (lower image).

Symptoms include pain, aching, discomfort, and feelings of weakness. Patients will sometimes, but not always, experience symptoms of instability. Instability is considered irregular movement within the joint that fails to keep the ball centered in the socket. Posterior instability can range from the ball moving slightly out the socket, to complete dislocation (ball is completely out of the socket). Oftentimes patients with this condition report a feeling of “looseness” in the shoulder. “Mechanical symptoms,” such as giving way, slipping, popping, catching, or clicking, are less common.

The most common cause of posterior instability is trauma. This can occur as a single event with the shoulder in an “at risk” position, like a blow or fall with the arms up or out. Posterior instability can also occur over time with repeated activity, such as the backhand stroke in racket sports, the pull-through phase of swimming, and the follow-through phases in a throwing activity or golf (1). In these athletes, intensifying pain is reported in the later stages of their sporting events or practices, when the joint stability provided by the shoulder muscles is decreased because of muscle fatigue (2).

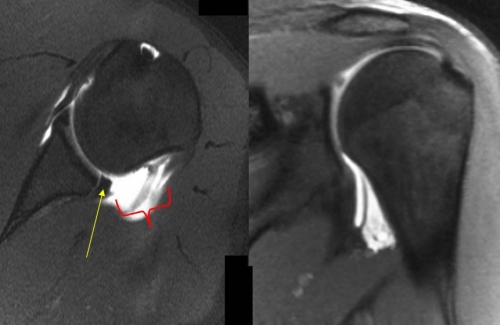

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is important in determining the shape of the glenoid (socket) in relation to the humeral head (ball). MRI will help determine any problems with the soft tissue around the shoulder joint. This includes injuries to the labrum or issues associated with the shoulder capsule.

This is an MRI from a patient who has suffered many dislocations out of the back of the shoulder, and has a compromised posterior labrum (yellow arrow). Without an intact labrum this patient will experience posterior instability. This patient also has a ruptured shoulder capsule (outlined in red) which is rare. The image on the right demonstrates a concomitant humeral avulsion of the inferior glenohumeral ligament (HAGL lesion).

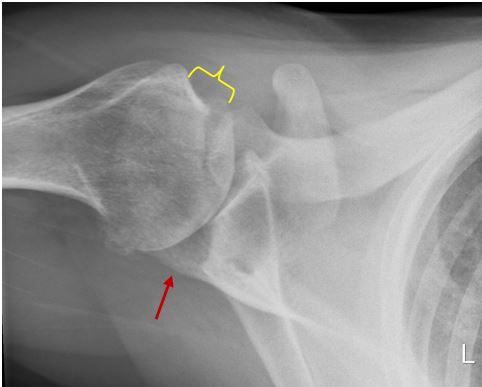

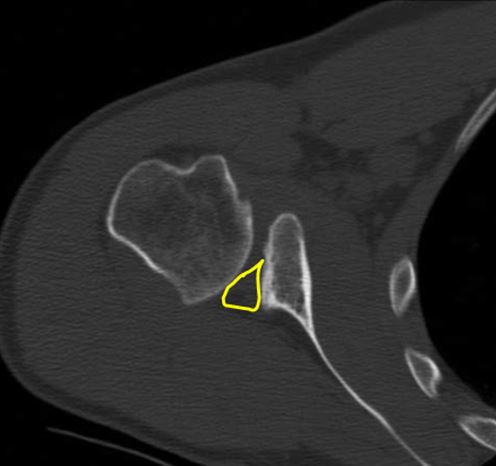

Computed Tomography (CT) may also be used. This helps further identify any problems with the joint surfaces that may be contributing to posterior instability. A CT can help define the size and location of a reverse Hill-Sachs lesion, a reverse Bankart lesion, posterior glenoid bone loss, or bony Bankart lesion.

This CT arthrogram demonstrates significant bone loss of the posterior glenoid (black arrows). The contrast dye (black spots) helps define the joint defects.

This CT arthrogram demonstrates significant bone loss of the posterior glenoid (black arrows). The contrast dye (black spots) helps define the joint defects.

In addition to imaging findings, your physician will ask questions regarding the history of the instability. A physical exam will also help your physician with diagnosing posterior instability, and determining the best treatment.

Nonsurgical treatment with physical therapy is usually the initial treatment of choice (5). This approach may be successful for some patients with recurrent posterior subluxation (partial movement of the ball out of the socket). Physical therapy will focus on strengthening the muscles of the shoulder, which will help stabilize the joint and prevent the instability. In addition to PT, activity modification may also be recommended. Several articles have reported that non-operative management is successful in 65%-85% of cases. (12, 13) PT has been shown to be less successful in patients with a history of a traumatic event (5).

If physical therapy fails, surgical treatment may be indicated. Patients with persistent pain, instability, or functional limitations may be considered surgical candidates. Patients who are very active, such as military personnel, are more likely to need surgical treatment as well (3). The procedures can be divided between soft-tissue operations and bony operations.

Soft Tissue Operations

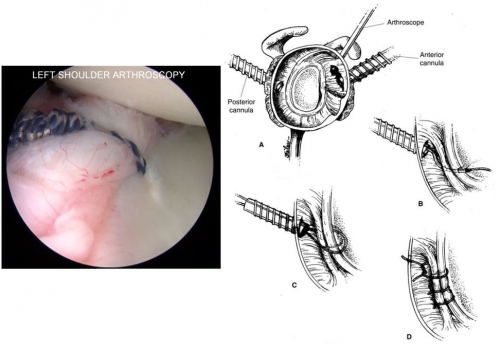

Soft tissue operations include surgical alterations and repair of the shoulder capsule and labrum. The shoulder capsule is the connective tissue that surrounds the joint, and it is very important for preventing improper movement of the humeral head into the back of the joint. Tightening the posterior capsule can help with instability. This is accomplished by tying down this capsule tissue and making it a stronger barrier against improper movement of the humeral head. This is done arthroscopically.

The labrum is a ring of dense cartilage around the edge of the glenoid (socket) that stabilizes the joint. A tear or injury to the labrum in the back of the shoulder, called a “posterior Bankart lesion,” can contribute to posterior instability. Surgically repairing the labrum is another technique to reduce instability. This procedure is accomplished arthroscopically, by tying sutures that repair and re-secure the labrum. These types of soft tissue procedures are referred to as “posterior capsulolabral reconstructions.”

The series of drawings (right) depict the arthroscopic technique of re-securing the posterior labrum with sutures. The image (left) shows the arthroscopic view of a suture that has re-secured the posterior labrum to the rim of the glenoid. (image at R from source 1)

Bony Operations

Bony operations enable correction of joint surfaces that are contributing to the instability. These types of procedures are indicated with the orientation or shape of the shoulder joint bones are contributing to instability.

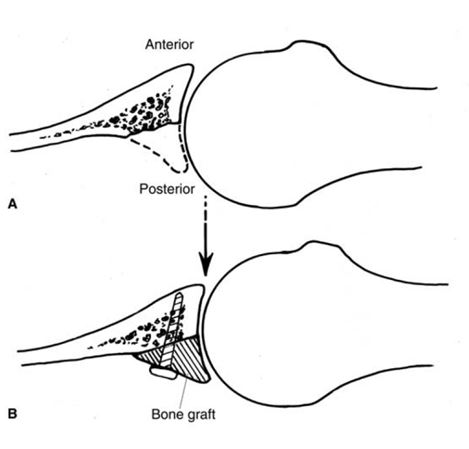

Many occurrences of posterior instability originate from acquired defects in the bones of the shoulder, either from a trauma or repeated activity. For these types of acquired structural issues, the glenoid socket can be reconstructed with a bone graft. In this procedure, bone is usually harvested from the patient’s hip bone. It is shaped to properly “fill in” the damaged part of the glenoid socket, and secured. As this bone graft heals and unites with the glenoid, it restores the normal curvature of the back of the glenoid socket, thus preventing further posterior instability of the ball. The bone used usually is taken from the patient’s iliac crest (area above the hip) on the same side.

Figure 6: (Top): Part A shows a glenoid that is eroded posteriorly, and part B shows how a bone graft would be secured to fix the defect. (Bottom): Post-operative x-rays from a patient who has undergone a posterior bone grafting procedure. (Source 1)

After surgery patients will usually wear a brace for 4 to 6 weeks, at the discretion of their surgeon. At usually 6 weeks, active assisted range-of-motion exercises are started. These exercises are overseen by a Physical Therapist, and help get the shoulder’s healthy motion back. Strengthening exercises are started 3 months after surgery. Patients are instructed to avoid collision sports for (at least) the first 6 months after surgery. These timepoints serve as a general outline of the recovery course. They will vary between patients, depending on how the healing is going. Your doctor will work with your physical therapist to help direct a personalized recovery regimen.

Most studies report on small numbers of patients and so it is difficult to reliably reference the literature on success of surgery. However, the clinical studies that are available indicate that arthroscopic treatment of posterior instability can be a very effective means to help even high-level, high-demand patients return to their activities and/or sports.

With arthroscopic capsulolabral reconstruction:

A 2005 article reported that in 33 cases of surgical treatment for posterior instability, stability was achieved for 88% of patients (at an average follow-up of 3.25 years). (6). (7) A similar article analyzed athletes in particular, and compared results between dominant-side shoulders in throwing athletes (27 shoulders) and dominant-side shoulders in non-throwing athletes (80 shoulders). While “excellent or good results” (relating to increased stability) were achieved in 89% of the throwing athletes and 93% of non-throwing athletes, the throwing athletes were much less likely to return to their pre-injury level of sport. Only 55% of throwing athletes were able to achieve their pre-injury level of sport. (8). Similar findings were reported in another study that looked at 200 athlete shoulders who underwent arthroscopic capsulolabral reconstruction: the authors found that while 90% of the patients were able to return to sport, only 64% of patients were able to return to the same level postoperatively (9).

With Bone-block Augmentation:

Mixed results have been reported with bony procedures to reconstruct the shoulder socket (see “Bony Operations” in Operative Treatment for description of the procedure). From a series of 19 arthroscopic posterior bone blocks (with average follow-up 20 months) the French authors reported decent outcomes. 9 patients had an excellent result (with return to previous level of sports) 6 patients were satisfied, and 3 patients had a consistently painful shoulder (resolved with further surgery). (10) 1 patient had continued pain and persistent instability. Another article reports a median 18-year follow-up on 11 patients who underwent a posterior bone block. 5 patients (45%) said they “would not choose the operation again,” and 4 patients (36%) had continued posterior dislocation/instability (11). This study showed poor long-term results of the posterior bone block procedure, although 3 patients with post-traumatic instability were pleased with the result of their operation. Based on your individual injury and goals, a discussion with your doctor will help direct the proper course of care.

- Millett PJ, Clavert P, Hatch GFR, JJP Warner. Recurrent posterior shoulder instability. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2006; 14:464-467

- Tannenbaum E, Sekiya JK. Evaluation and management of posterior shoulder instability. Sports Health 2011; 3:3

- Antosh IJ, Tokish JM, Owens BD. Posterior Shoulder Instability: Current Surgical Management. Sports Health 2016

- Delong JM, Kiang J, Bradley JP. Posterior Instability of the Shoulder: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of clinical outcomes. Am J Sports Med 2015, 43:1805

- Provencher MT, LeClere LE, King S, McDonald LS, Frank RM, Mologne TS, Ghodadra NS, Romeo AA. Posterior Instability of the Shoulder: Diagnosis and Management. AJSM 2011 39:874

- Provencher MT, Bell SJ, Menzel KA, Mologne TS. Arthroscopic treatment of posterior shoulder instability: results in 33 patients. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33(10):1463-1471.

- Bradley JP, Baker CL 3rd, Kline AJ, Armfield DR, Chhabra A. Arthroscopic capsulolabral reconstruction for posterior instability of the shoulder: a prospective study of 100 shoulders. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34(7):1061-1071.

- Radkowski CA, Chhabra A, Baker CL 3rd, Tejwani SG, Bradley JP. Arthroscopic capsulolabral repair for posterior shoulder instability in throwing athletes compared with nonthrowing athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36(4):693-699.

- Bradley J, McClincy M, Arner J, Tejwani S. Arthroscopic capsulolabral reconstruction for posterior instability of the shoulder: a prospective study of 200 shoulders. The American Journal Of Sports Medicine [serial online]. September 2013;41(9):2005-2014. Available from: MEDLINE Complete, Ipswich, MA. Accessed December 6, 2016

- Schwartz DG, Goebel S, Piper K, Kordasiewicz B, Boyle S, Lafosse L. Athroscopic posterior bone block augmentation in posterior shoulder instability. JSES (2012) 22, 1092-1101.

- Meuffels DE, Schuit H, van Biezen FC, Reijman M, Verhaar JAN. The posterior bone block procedure in posterior shoulder instability. JBJS (Br) 2010; 92: 651-655

- Burkhead WZ Jr, Rockwood CA Jr: Treatment of instability of the shoulder with an exercise program. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1992;74:890-896.

- Hurley JA, Anderson TE, Dear W, Andrish JT, Bergfeld JA, Weiker GG: Posterior shoulder instability: Surgical versus conservative results with evaluation of glenoid version. Am J Sports Med 1992;20:396-400.

Images

Football player: From youthfooballonline.com

Skier: From the Denver Post

Posterior direction illustration: From Medical Multimedia Group

Arthroscopic and bone graft illustrations: Above: From Millett PJ, Clavert P, Hatch GFR, JJP Warner. Recurrent posterior shoulder instability. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2006; 14:464-467 (source 1)